In this era of ‘Big Data’ buzzwords flying everywhere, “We at FilmProfit prefer to focus on the accuracy and the appropriateness of data, not its height or its girth.” FilmProfit Uses Latest Data Science Techniques to Guide Financial Modeling Deep knowledge of the

Continue ReadingHow Do We Arrive At A Film’s Projections Model?

Are They Predictions?I find that some folks prefer to look at Projections as some kind of prediction of performance. Let me start off by saying clearly that Projections of Potential Income ARE NOT PREDICTIONS of any performance. Predicting is what humans have sought for

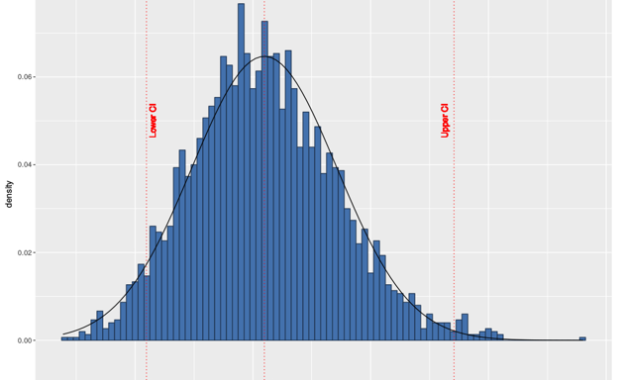

Continue ReadingAnnouncing A New Product, Statistical Confidence Modeling in Film Projections

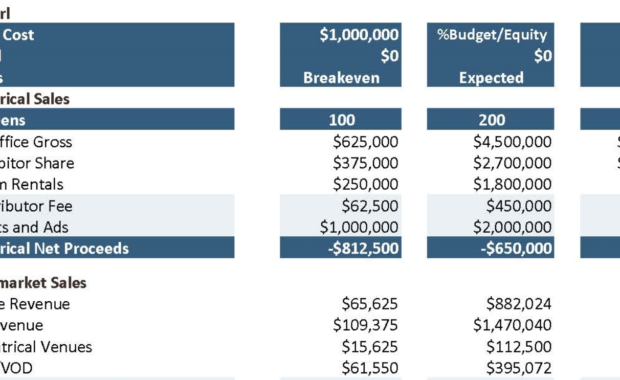

Bootstrapping Our Way to Confidence and Probability Over our 25 years of financial modeling for films and slates and funds, we have developed sophisticated methods for modeling a film or films in distribution. Because of our hard-won proprietary data and years of deep

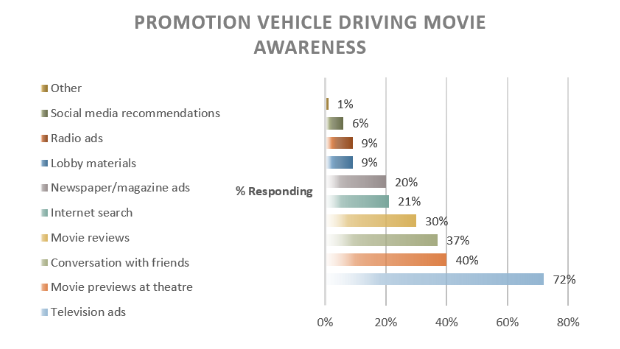

Continue ReadingBig Changes Coming to Landscape of Film Marketing

Television, The Big Elephant in the Room, May Be Shrinking The number one single cost in releasing a film to theaters has been the buying of television ads. For many studio films, this can run from $4 million a week to $15 million a week in the month to six weeks

Continue ReadingComparable Pictures: How to Choose ‘Em and Use ‘Em

I get a lot of clients who find it difficult to choose comparable films right off the bat. I wrote this article to help them, and help others, even if they do not become clients. Bona Fortuna to all! How I Go About Choosing Comparable Pictures In a given year I might

Continue ReadingFilmProfit Glossary of Film Terms

This is a Glossary of Key Terms Above The Line Budgets for films usually begin with a section that covers creative talent such as: actors, directors, producers, and writers. This section is followed by the rest of the budget, or Below the line. This term also refers to the

Continue ReadingKey Risks In Making A Film, & How to Manage Them

If you're in the film business there's a good chance you've read a statement like this before: Statements like this usually go on half a page or more, listing a pile of risks, including competition and the like. But I am focused here on the specific risks a producer

Continue ReadingComparable Pictures: How to Choose ‘Em and Use ‘Em

I have helped producers choose and use literally thousands of titles for comparison to the films they seek to finance and make. When I am preparing projections and financials packages, whether for a single film or a slate of films, the first crucial task for me is to

Continue Reading