If you're in the film business there's a good chance you've read a statement like this before: Statements like this usually go on half a page or more, listing a pile of risks, including competition and the like. But I am focused here on the specific risks a producer

Continue ReadingComparable Pictures: How to Choose ‘Em and Use ‘Em

I have helped producers choose and use literally thousands of titles for comparison to the films they seek to finance and make. When I am preparing projections and financials packages, whether for a single film or a slate of films, the first crucial task for me is to

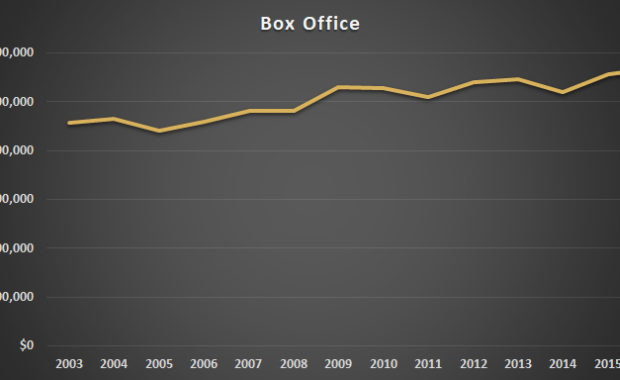

Continue ReadingBox Office Panic! Part IV

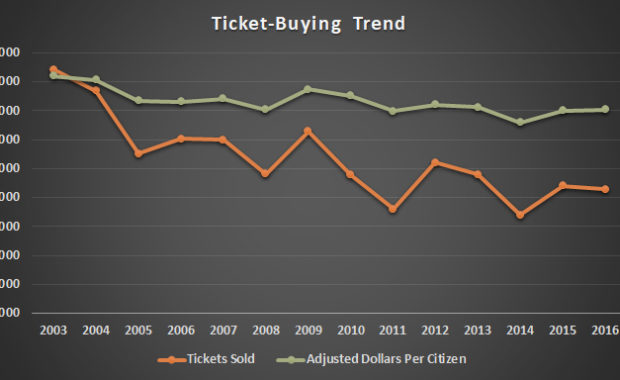

What Chance Do Indie Films Have? Over the last three weeks, I had wanted to explore whether, as some were intimating, the idea of going to see movies in theaters is a dying market. Hi Def TVs, Netflix and Amazon around the world, TV downloadable to mobile devices, couch

Continue ReadingBox Office Panic! Part III

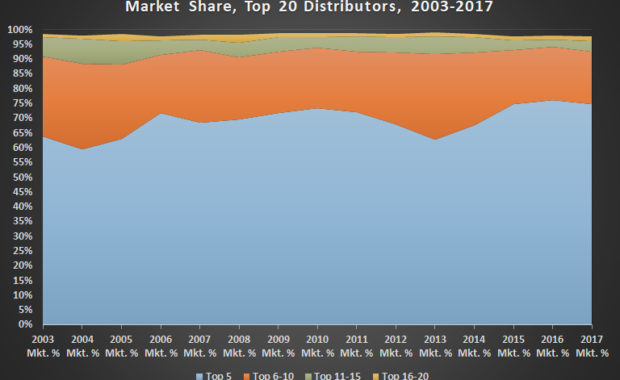

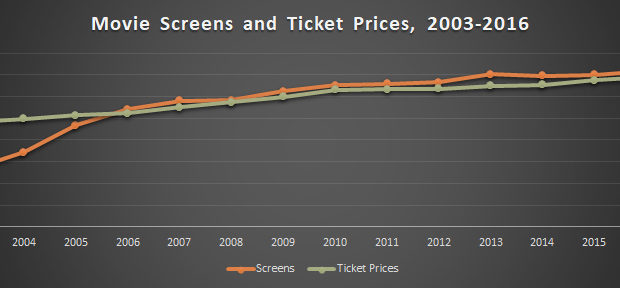

Last week, I discussed box office, primarily by quarters over the last nearly eight years. I hinted that I was going to go in a slightly different direction to see if we can discern if there are fundamental elements causing this to play out the way it does, and who is

Continue ReadingBox Office Panic! Part II

In my previous installment of this probing into the health of the movies in theaters business, we looked at two rudimentary charts that showed that, though the industry touts the fact that box office goes up each year (kind of like a public company report that wants to say

Continue ReadingBox Office Panic! Part I

Some in Variety, in the Hollywood Reporter and other outlets have been panicking that this down movie ticket year is the death knell of movies in theaters. I am no Pollyanna, but I heard this story in 2005 as well, of course coming off of the sterling year which brought us

Continue ReadingHow Do You Kick-Start Your Business Plan?

What The Heck Is The Thru-Line? And Why Is Every Film A Marketing Challenge and An Opportunity? ***I am updating this article, particularly after a discussion with a client that tweaked my thinking on using the word “problem.” Every time I used it, I found myself

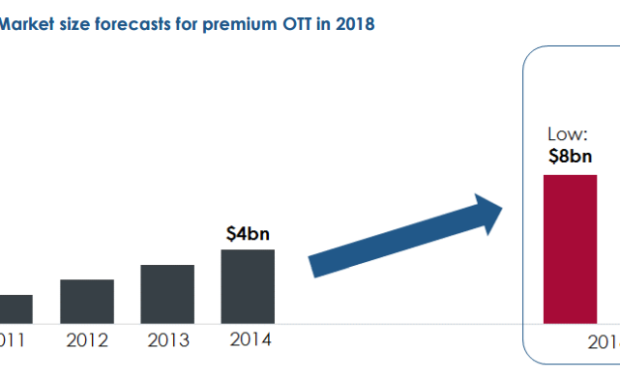

Continue ReadingWhy is Video on Demand so Attractive?

And Why Are So Many People Mystified About Video on Demand and Its Contribution to a Film’s Value? It’s attractive because delivering a film is expensive, and the core purpose of filmmaking is sharing what you made, the story you have told. More ways to share it are

Continue Reading